The starting point for a true criticism is found in the works of art. True, but how does one understand, interpret and explain a complex artistic phenomena like Gaganendranath Tagore? Critic’s attitude to Gaganendranath’s Paintings can serve as an example of a kind of indentification of the style with the artist. Although Gaganendranath used several different styles, it is odd that he is only identified with one, and if critics have ever mentioned about the various styles/phases of his work, it is merely to demonstrate that they are not the essential Gaganendranath.

Now, what is the essential Gaganendranath? Critics like Asok Mitra, Jaya Appasamy, Ratan Parimoo and Benode Behari Mukherjee discovered an aspect of Gaganendranath which they were prompt in proclaiming as the essential one, essential not only in relation to Gaganendranath’s whole work but also in relation to his whole spirit. The painter is identified with only one phase of his paintings, i.e., his cubist phase:

Strangely enough both Rathindranath and Dinesh Sen have omitted the cubist pictures from their account of Gaganbabu’s painterly pursuits’.

Why this overemphasis on the cubist period? For some critics the essential Gaganendranath is his cubist period. But on the whole, the idealist criticism presented comedy (comic/caricature) as an art form of only secondary importance. It is generally considered as among the lower genres of creative expression and is regarded as its province man’s base and more primitive emotions and aspirations.

However, as an Art historian I have to confront manifold problems:

1.Why did Caricature as a form of artistic expression emerged during 1917-1921 and that too almost entirely through Gaganendranath’s unique talent?

Caricature tradition in India (or to be specific in Bengal) is not a continuous one, this particular form emerged only at certain historical times (for instance during 1850-1880 and again during 1917-19211. Why does a particular art form disappear and reemerge at indefinite intervals? Is time not divided into periods of art history which in fact form a chain of successive styles (Post-Impressionism, Cubism, Fauvism, Constructivism etc)? Actually the problem can be posed like this:

1.Does the history of art really have a history?

2.If so, then what is the principle on which it is divided into periods?

Accepting this suggestion would mean that one accepts the relative autonomous existence of creativity (Production of pictures) and art. This is not only straight- jacketing the development of art and history of a society, but it is also vulgarisation of the concept of creativity in a complex world and society.

Really speaking, can creativity and art exclude its ‘dependence on other histories, say for example, modes of economic production, the religious, social and political aspects or other relatively autonomous history of a society? Max Raphael stated long time ago:

Art has historical roots that lie outside it, and it has historical consequences that again lie outside it. .. Art as such has no history.2

Thus the division of time into periods is in general linked up with the mode of economic production.

But within the definite historical condition, one can find the co-existence of several and different visual trends (which may appear and disappear during the epoch), but this one to one relation between art, history and mode of production presupposes that all the different and opposing trends in art are only variants of one major structure. Here, from the above paragraph two problems emerge:

- Art forms may appear and disappear in a given epoch.

If one looks at the chronology and development of Gaganendranath’s artistic career it is clear that the cartoon period takes place in the middle of his artistic persuit, i.e., before and after, of divergent artistic content and styles.

What is interesting to note that generally speaking the various phases in Gaganendranath’s career do not relate to each other, there is no sequence of development from one content to another, or of one style and technique to the other for that matter and finally the cartoons (as an artistic genre) never reappear either in his life or later in the subsequent growth and development of contemporary Indian art. So I would go back to the problem: why did it appear and disappear?

Was this particular genre painting historically bound to occur between 1917-1921, and why only through one of the major artists of the time and not anyone else, and why such authentic force and character compared to the caricatures of either belonging to the nineteenth century Bengal and of the works of other minor contemporaries of Gaganendranath?

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

The first Modern Indian art movement was born out of the cultural regeneration and was part of the nationalist movement. The works of the Bengal school artists were generally acclaimed and accepted. But:

Gradually the bias that gave dominant nationalist overtone to art was exposed to the fungus of a strange Parochial nationalism. .. the Modern Indian painters displayed his remoteness from tradition by misunderstanding the function of traditional art in the modern environment. 3

In the changing social and cultural circumstances, the Bengal school artists painted the same subjects-over and again in the same manner. Their work became manneristic. Qualitative terms like ‘spiritual’, ‘mystic’, ‘rhythmical’, and ‘Lyrical’ came to be associated with their works. Concern was voiced by Coomaraswamy:

They have been anxious to make beautiful pictures, rather than moved by sheer necessity of expression 4

It may be said without fear of contradiction that our present poverty, quantitative and qualitative, in works of art, in competent artists, and effective connoisseur-ship is unique in the history of the world.5

But why Bengal school remained a “narrow ridge” (actually spanning from 1905 to 1920, i.e. beginning from the time when Abanindranath painted ‘Bharat Mata’ and till be gave up brush and paint temporarily in 1920), a ridge which could be crossed the moment it was reached? A style which apparently looked solid, based on conservative, formal principles of Indian Classical art, on a technique brilliantly innovated by Abanindranath (wash) and on the lofty ideals of spirituality and humanity, what made it crumble like a pack of cards? Why did it degenerate so quickly into mere imitation of Ajanta and Mughal miniatures? Perhaps the artistic expression of the Bengal school was more an ideal and a fiction than a reality. And unlike the European Renaissance which was very dynamic and the artists restlessly searched for new forms to master the complexities of the ever changing capitalist mind (and in the process the Renaissance lost the classical balance and poise), the Bengal school was rather weak in constitution. It rested on its achievement [as if in deep aristocratic slumber) and was never eager or able to master the rapidly changing society in general. They lost touch with the new scientific out-look and development, and with the modern cultural developments.

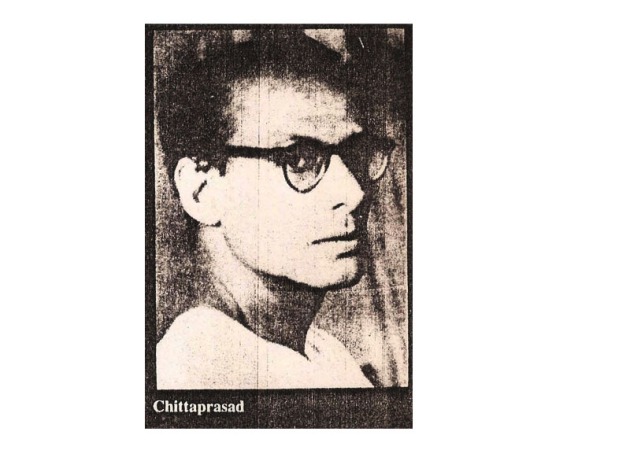

Gaganendranath was an untutored artist [like his more famous uncle Rabindranath) and emerged as a serious painter at the age of forty three, i.e. around 1910. His early works “Sibu Kirtaniya’ dated 1907 and ‘Crows’ dated 1910 express the desire to maintain the unbroken continuity of the artistic process of the Bengal school. But nevertheless we notice the free gesture in ‘Sibu Kirtanya’, the roots of his future departure from Bengal school is inherent in the particular work, or rather the ambivalent nature in relation to Bengal school is expressed here, this ambivalence takes the final shape and form, in an utterly un classical spirit [to take place after 1917). Gaganendranath perhaps realised that the contemporary reality had nothing to do with available range of cliché images, that it was necessary to discover new situations characteristic of his time and to build up new, powerful un -hackneyed images. Myths and legends were no longer a reality for him. This search for the new Indian Picture-book revealed the extraordinarily subtle form of social criticism went far outside and beyond the – feeble imitation of the mannerist phase of the Bengal school. The method of the un classical was not only able to regain the lost reality but it also created a new art form, which is unique in the history of modern Indian art. Now I will return to the second problem raised earlier.

- All the different and opposing trends in art are only variants of one major structure.

….. all visual ideologies corresponding to the capitalist mode of production (from the ‘early Renaissance’ to ‘cubism’) have a common structure which is clearly distinguished from the structure of visual ideologies of the ‘feudal’ mode of production, or of the ‘Asian’.6

Here the problem is two-fold

1.The Western Capitalist Society under which content and form of all art comes under one common structure. I am sure this one-sided judgement would raise many objections. It has often been pointed out that extremism is one the chief characteristics of the modern movement in art – post-Impressionism, cubism, expressionism, surrealism and so on. Generally this is true: But again generally all capitalist art is Romantic, in the sense that most of the modern western masters revolted [in each movement or ‘isms’ of art) against the bourgeois condition. John Berger sums this up very well:

….. were aware of the feebleness and corruption of bourgeoisie art and values and they all sensed that the twentieth century would produce a new type of man who they wished to welcome ….. They knew that they lived on the eve of Revolution, and they considered themselves revolutionaries.

But because they did not understand the social and political nature of this revolution, they put all their revolutionary fervor into their art… 7

They made revolution on their canvases. Whether logical development or not each art movement was a departure from the previous one, sometimes a drastic one for that matter, Surrealism was for removed from Cubism, so is OP art from the Abstract. If all bourgeois art is reactionary, decadent, defeatist and formalist, then we will have to admit that there is no progress in art other than what is being and would be produced by the socialist artists.

Bourgeois artists do take part in the discovery of the world in which we live in and in the artistic expression of the complexities of life and society. Their work is a sort of negation of the existing situations, through which there is a way we can advance. But Marxist art critics may still consider it as the negative role of the bourgeois artists. The question will be: are the bourgeois artists capable of creating new content and form altogether different from another art form or style? In a capitalist society the artists [vis-a-vis, their position as Avant-garde), have the freedom and are capable of creating the kind of art which they want and need. Chaplin through his grotesque parodies of everyday life exposed the bankruptcy of either fascism or of the machine age, and then heralded the victory of man, though not like Eisenstein, but still a victory all the same, and in the process evoked a new cinematic form: comedy/satire or whatever one may wish to define; and now let Ernst Fischer speak for Picasso’s “Guernica’

Picasso, using the painter’s means, showed a world blown into a million pieces, not as an expression of anonymous fate or as a cosmic event but as Guernica, as human existence threatened by Fascist dictatorship. This magnificent painting does not merely represent reality in its most concentrated from: it sides with tortured humanity …. If these were a case of so-called “formalism’ Picasso would not have called his work Guetnica, but Explossion, Destruction, Under the sign of the Bull…when hundreds of genre paintings and academic historical canvases that hope to pass as realistic, have long been forgotten, our great grandchildren will recognise a chronicle of our lives in the bitter, extreme Realism of this tremendous work. 8

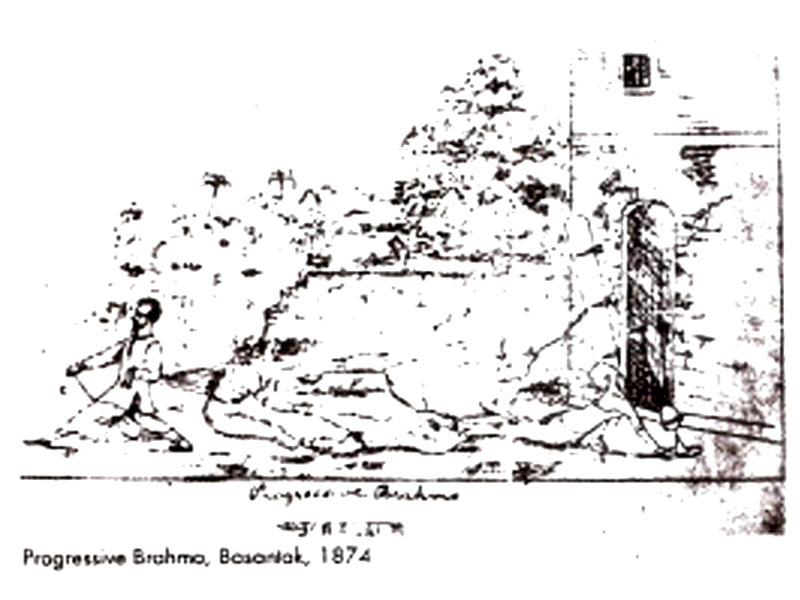

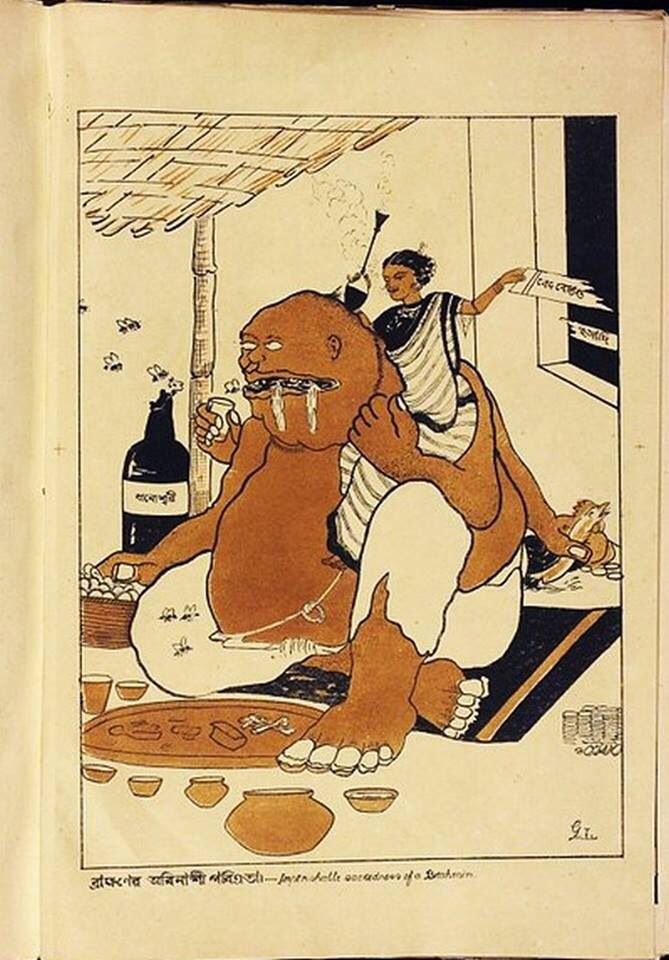

Kattamoshai, Harbola Bhad, 1st Vol., 1st number,January,1874

I would like to assert that Guernica had no precedence either in the content that it conveyed or its form. And neither there is any following of this form. Can we call this work Realism? Yes perhaps, but it falls short of socialist Realism only because it uses symbols and allegories. Now-let us see the other side of the coin i.e. bourgeois/capitalist art in the context of the Asiatic Mode. Art and culture under the Asiatic mode of production is bound to develop in a different way, the form it takes, the style which individual artists are able to arrive at, will be different also. There is nothing peculiar about it, but the question is to what extent the art (of each country, of each time and age under the Asiatic mode) is able to preserve its own peculiar characteristics, its identity ( to the extent of keeping in fact the authenticity of the works, which could be discussed at any time in history). Or in other words, suppose I put the question this way: to what extent is Indian art Indian, National and International? To be more specific, as is the case here:

- To what extent Gaganendranath was an Indian artist, whether he was rooted in the peculiar social reality of his time, whether his form and style was Indian, how much was he International or cosmopolitan?

2.Was his art a mere variant of the other trends prevailing in Bengal at the time? Or was

it an extreme variant, a completely new type of art?

Rabindranath Tagore described him as a jovial man who would keep them in good humor all the time. Dinesh Chandro Sen, a close associate of Gaganendranath paid rich tribute to this large hearted kind and gentle nature d men.9

Gaganendranath was born to a rich and aristocratic joint family, but, he had to bear the responsibility of the family (at the age of fourteen) due to his father Gunendronath’s untimely death.

This awesome responsibility that he had to see his two younger brothers { both of them artists, Abanindranath and Samarendranath get necessary education, made it almost impossible for him to take the necessary education {for a brief period he went to St. Xavier school, Calcutta}. Later he was involved in a legal battle with Debendranath’s family on the question of ownership of family properties. 10 However, It is beyond doubt that he lived in the same house [i.e. Jorasanko House at Calcutta) where Tagore also lived. Not only that, we see him actively organizing and taking part in the various social and cultural programmes which the house of the Tagores initiated right from 1897 to 1919. Whatever little evidence we have at our disposal of the biographical details of Gaganendranath, it can be safely said that there was nothing satanic in him, he was not of the hissing and whistling type like the other feudal aristocrats of his time. The Tagores’ often indulged in simple and pure fun. The great difference being, that they channelized all their energies, their sentiments, emotions, innovativeness and skill to art. One would not find a single member of the entire Tagore clan who did not either know how to paint, sing, dance or write poetry. Art and culture practically got concentrated around this family.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

But despite the stupendous achievement the family made in the field of art and culture, I am inclined to make this observation that perhaps the family was cursed, some ultimate doom was hanging large on them. Tragic incidents took place almost at regular intervals, untimely deaths, suicides of the young ones, Gaganendranath’s illness (he became paralytic during his last ten years, 1928-1938). Abanindranath’s utter frustrations in the last years of his life over the apparent failure of the art movement which he led with conviction and dedication, the split in the family-due to property feud, and finally the decline in the family capital ( It came to such extremes that many household items had to be sold out, which included books, art objects etc], contributed to the ultimate tragedy. The mess in the financial position was largely due to their own failing. As early as 1893 Surendranath Tagore sent a warning from Woodland House, Shimla to the Jorasanko house: “No one is really concerned to look for a livelihood.”11 Everyone of the family depended entirely on the earnings from the landed property and whatever business they inherited.

But despite these gloomy family circumstances the Tagores found time to indulge in idle fancy. As early as 1897, on the proposal of Rabindrnath and Gaganendranath, a club for the whimsical s/eccentrics (in Bengali: Khamkeyali Sabha) was formed. The club did not really mean any serious business, but the occasional meetings paved the way for the Tagores’ as well as other whimsical artistic members to get together and enjoy the evenings.

It seems, sense of wit and humor were natural to the Tagores’. Gaganendranath, especially, had a magnificent, elemental wit which provoked sparkling waves of laughter. But at the same time he was perhaps the saddest, the most tragic figure among the Tagores. Was there any “unseen tears” in him? We do not know for sure, but the quotation he used of Mark Twain in the first page of his book on cartoons, “Nobo Hullor’ (Reform Screams) will make everyone to ponder over it:

Everything human is pathetic, the secret source of humour is not joy but sorrow. There is no humour in Heaven 12

Before I proceed to discuss the actual cartoons, I would like to answer a few questions which seems crucial to me:

1.How was his contribution an extreme variant?

His contribution towards modern Indian art was extremely different from that of his own contemporaries only when we consider him as a caricaturist. During the period three main art trends were prevailing, two of them, i.e:

- The nationalistic bourgeois style (which is the so called Bengal school]

- The Western Academic style was on the wane already. And the third trend was kind of a mixed bag, something which some of the Bengal artists like Mukul Chondrc Dey, Manindra Bhusan Gupta, Ramendranath Chakravorty did not toe either of the two trends mentioned above. It was kind of naturalism (which I think went back to the tradition of Emily Eden, Solvyns, William Hodges and W.B. Atkinson the residing British artists in the eighteenth and nineteenth century Bengal]. Let me mention at this point that naturalism was another though less important trend (according to the Archer’s school of art historicism] nonetheless, it did influence the Indian artists of the Patna and Murshidabad school.

Rabindranath Tagore who along with Abanindranath and Gaganendranath worked hard in establishing the Bichitra Club at Jorasanko House rightly assessed the contribution of Gaganendranath:

During this period Gaganendranath discovered a new medium for giving expression to his fund of humour and satire in caricatures.13

It is assumed that some of his cartoons were initially published in various magazines at Calcutta, and realising the demand, Gaganendranath decided to publish them in book form, especially in lithograph technique. For this purpose an old litho press was purchased and with the lithographic (an old Mohammedan printer was appointed especially to help Gaganendnath in lithography technique] equipment a new section was added to Bichitra Club. In 1917, Gaganendrnath’s colour lithographic cartoon album ‘Adbhut lok’ 1917, (Realm of the absurd] was printed in this press. Gagenendranath was clever enough to take the opportunity of mechanical printing to popularize his cartoon.

Apart from creating a new art form, Gaganendranath’s interest in graphics (or for that matter Bichitra Club’s] initiated a new meaning in the Modern Indian art movement. Graphics or print making, introduced by the British in the art schools, was mainly used for re-duplication of pictures or’ for illustrations of books to make it interesting for the newly growing reading public in Bengal. Outside the Art Schools, printmaking was already in vogue with the private studio-owners but it served mainly as a mass-communication media rather than as a creative medium. From the first illustrated book (printed in 18161 to Gaganendranath it took more than hundred years for the Indian artists to give certain prestige and stability to the graphic medium as a whole, which Europe had achieved at least a century back.

Comic art has its roots in the ancient past. There are examples of humorous representation in the art of almost all the cultures. According to Hofmann and Becatti,14 comic art generally originated (both in Asia and the West from Drama. Both the visual arts and the drama found comic themes in daily life, and such personalities as the vidusaka, or buffon appeared in those media in India. Comic art was not unknown to ancient Indian art. But it occupied a minor place in the field of art. –

Most of the humorous incidents depicted in the arts relate to simple facts of life, like eating, sleeping, and the deformities of the human form… the purpose was to idealize rather than to caricature 15

Besides, the social life did not leave any scope for the artist to caricature kings, brahmins, social customs and manners. But the most important factor that why it could not develop as a full genre art in India till the middle of the nineteenth century is due to unavailability of printing technology (multiple reproduction system], lack of education among the people, an enemy (alien to the soil] who could be treated as satirical themes etc. The obstacles were cleared by the colonial rule or through their regeneration work.

Ironically, it was the British who introduced modern comic in Indian art during the middle of the nineteenth century. But it remained confined to Periodicals/Journals only, it had to wait till Gaganendranath’s advent into this category of art who transformed cartoons as display print or work of art from the normal prints published in the journals.

Delhi Sketch Book a monthly periodical published from Delhi in 1850 pioneered the art of modern caricature in India. Its founder editor was John O’ Biren Saunders. (?-18791). Saunders was succeeded by George Wagentrieber. The periodical wound up in 1857. Available Cartoons published in Delhi Sketch Book do not bear signatures of the artists. But one can probably assume by looking at the cartoons that they were mostly executed by the British artists. It satirises life styles of the British in India. This was followed by Indian Charivari (in the footsteps of London Charivari ) which started appearing from Calcutta in 1872 and was edited by Col. Percy Wyndham. It is difficult to ascertain the identity of the cartoonists who contributed to these periodicals. The first newspaper to publish cartoons was ‘Amrita Bazar Patrika’, in Calcutta (18721. From then on, a stream of comic periodicals started appearing in various cities of India and in different languages:

Bengal: The Sulav Samachar (18701)

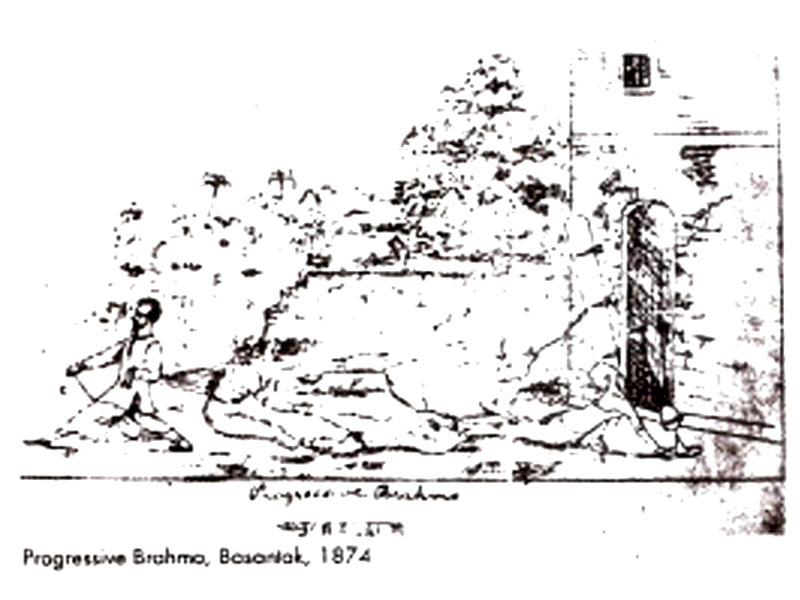

Harbola Bhad (18741)

Basantck (1874)

Lucknow: Oudh Punch (1877)

Western India: Parsee Punch (1888).

The artists who contributed in these journals were mostly Indians. Cartoons never ceased to appear in Bengal once it started in 1850. At the turn of this century a number of newspapers like the Englishman, The Statesman. The Patriot, Indian Ink, The Bengalee introduced cartoons. But it always kept a low profile, being dominated by the British academic art, the Bengal school and huge upsurge of book illustrations and Kalighat Pata Paintings, it also needed a brilliant educated intellectual like Gaganendranath who could counter the vices of the society in all its aspects and spring off an highly original and personal style. But did he make sufficient number of cartoons:

- So that it makes a solid body of work?

- To deserve any serious discussion?

- To its being termed as a new genre painting?

Accordingy to O.C. Ganguly Gaganendranath painted about five hundred cartoons.16 Art historians O.C. Ganguly, Kamal Sarkar and Sovon Som agree that Gaganendranath played a pioneering role in this particular category which in the context of his own time and today is valid and relevant and of course it deserves serious attention and discussion which is unfortunately very scarce. Gaganendranath’s cartoons can be divided into four categories:

- Social b. Political c. Religious d. Educational.

Apart from the numerous cartoons published in various newspapers, magazines (and some untraced, missing, etc.] he published three albums on cartoons:

- Birup Bajra (1917) Strange Thunderbolts.

- Advut lok (1917) Realm of the Absurd.

- Naba Hullor (1921) Reform Screams.

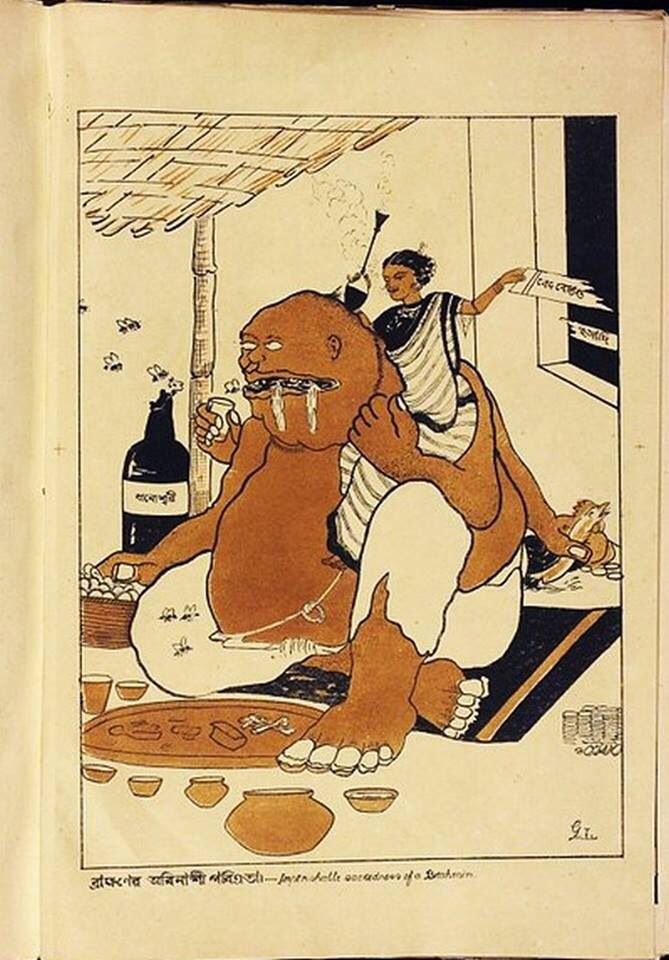

Birup Bajra (Strange Thunder-bolts) 1917

This album includes thirteen colour and black and white cartoons with an introduction by the famous scientist Jagadish Chandra Basu. This album falls into the category of social.

What is the meaning of Gaganendranath’s cartoons?

Auto-Speechola or An Automatic speech making machine

It satirizes the Rajas and Maharajas of Bengal who delivered lectures on various subjects in public prepared by others. The Puppet like doll is the symbol of an aristocratic person. He is, holding a copy of the speech in his left hand. A dagger is tucked into the waist band, and he is speaking through a hand mike. An oil-con is fixed on the top of the head, just because he is like a machine. The puppet is supposed to be run by an ‘auto-speechola’ machine discovered by some scientist of Bengal. It is some sort of a computer which has been fed with the ready made speeches on various topic like Memorial speech, Self-Government speech, Foolish speeches and Fiery speeches in English, also there is a set of Bengali speeches on different topics.

Advut Lok (Realm of the Absurd) 1917

The album opens with two quotations

1.To be foolish is human.

To laugh at it so more so.18

– Rabindranath Tagore

2. Instead of feeling complimented when we are

called an ass,we are left in doubt.19

– Mark Twain

Gaganendranath was an artist-thinker. The thinker and the artist in him was magnificently combined. The brilliant images are contrasted successfully by linking of two contradictory elements. This is essentially possible when the artist has wit, sharp and simple. Wit was Gaganendranath’s element.

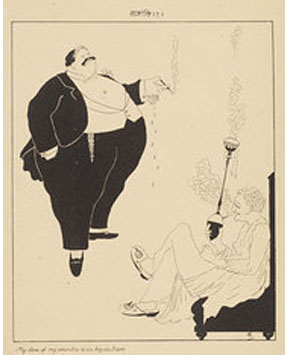

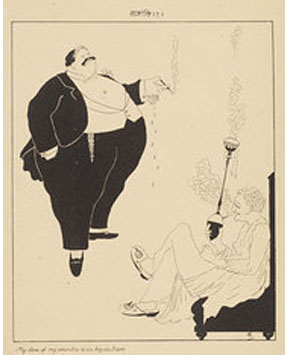

My love of My Country is as Big as I am

Here, notice the inflated figure of Maharaja Bijayachand of Bardhaman (Bengal), holding a cigar in his hand, Bijaychand was indeed a hefty fellow. He had English manners and dressed like the British. He went on lecturing about his love for the motherland. This was the contradiction among the educated and aristocratic people of Bengal. Now, notice the middle aged man listening to Bijaychand’s lecture. He is in simple Bengali dress, holding a traditional hukka in his hand; in contrast to Bijaychand’s huge figure, the other Bengali gentleman looks frail and small. He is supposed to be Gaganendranath himself, enjoying the lecture immensely. The artist employs his wit by uniting dissimilar characters, ideas and demotion. Similar is the case with

A Noble Man

The figure resembles that of Maharaja of Bardhaman. The rich noble man is elevated to a pedestal used for worshipping gods and goddesses. Notice the rickety hands extended towards him for help which he wipes off by the sweep of the stick. The neo-rich of Bengal in those days used to spend lavishly for. vulgar purposes such as on horse race, kite flying and of course on prostitutes. A symbolic hand of a prostitute is shown extended towards him. Look at the vultures around him, they were symbols of posychophants who gathered around him for money.

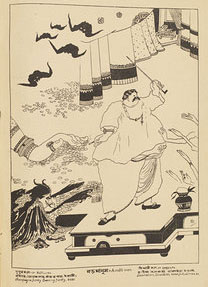

Naba Hullor (Reform Screams) 1921

Where is H.E.

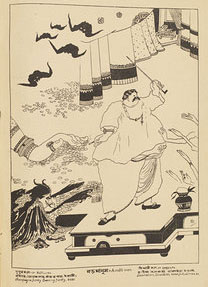

This was done on the occasion of lord Sinha’s (1920-21) appointment as Governor of Bengal (first Indian Governor during the British Rule). It seems a vision from below. The aerial space and earth is indicated by simple division in black and white. But aerial space (top left) and the earth is on the same plane. A very rare compositional structure for a cartoon.But it is more like a painting, In political cartoons minimum space is used, and the figures reduced too much or blown up out of proportion, I would like to mention here the striking similarity of this cartoon with Soul Steinberg’s “Drawing of the Galleria in Milan, 1954”, However, this cartoon depicts several Governors (with their ADC’s) who all look alike,State Funeral of H.H. old Bengal

Purely political cartoon, based on Montagu and Chelmsford (Montford Reform) of 1919, which promised Diarchy (double rule). Followed by the Home Rule, prisoners were released, (Earlier Tilak and Annie Bessant established Home Rule league and All India Home Rule League in 1916). The Montford Proclamation dismissed the old Bengal Legislative Council and though it promised to empower the provinces towards establishing self-government and self-determination, in reality this act helped the British to suppress individual rights and sentiments for agitating in terms of Independent political power by the people of India.20

The cartoon shows a long dead body (of the old council) carried by its members, The members have been identified as Maharaja of Bardhaman, Sir Samsul Huda, Sir PravasChandra Mitra, Bhupendra Nath Bose and Babu Musaraf Hussain.21

Large numbers of people are witnessing the funeral. Surendranath Bandopadhyay is playing the drum in front of the procession (it is witnessed even today) and a press photographer is desperately trying to take a photograph of the important event. Maharaja Manindra Chandra is sitting on the veranda of his house (and smoking a hukka) and enjoying the happenings. Again, look at the use of space, where the drama takes place. The space becomes large because the artist is narrating a story. This is important in Gaganendranath’s cartoon: the narrative cartoon. This is unique in the history of Indian cartoons. The artist’s tendency in the cartoon is the economy of line, space, size (of the cartoon) etc. Gaganendranath sets his cartoon in the style of a painting

Latest Flight of the Poet

No one, not even his uncle Rabindranath was spared by Gaganendranath. This is a caricature of Rabindranath. The poet is seen flying seated on an easy-chair. Starry sky and half moon, his fountain pen, manuscripts flying, he is holding an Ektara (one-stringed musical instrument) and it is looking on with wondering eyes.

It was time of the non-cooperation movement and everybody was eager to know the poet’s opinion on the subject but he was abroad at the time. Incidentally this was his first air travel (he left for London on 16th April, 1921) and before his departure Mr. St. Nihal Singh took an interview of the Poet:

…. I learned that he and his party were to go to the continent by air. 1asked him if that would be his first flight. Quick as 0 flash he replied that he had been flying all his life, but this would be first of that sort. The latter port of his sentence was drowned in laughter. 22

Perched on the nib of the fountain pen are inquisitive journalists trying with their telescopes to discover which side of the earth is the destination this time, whether the region is the region of cooperation or non-cooperation? Rabindranath attracted the artists’ imagination. He was not only handsome but he also had a sensitive face which prompted two of the finest sculptors of the modern era to make portraits [locob Epsteine and Ramkinkar BaiiJ. Besides, Gaganendranath, he was caricatured by several European artists. Cartoons on him were published in America (Ohio State Journal), England (Manchester Guardian), Germany (Simplizissimus), in Switzerland and in Egypt.

Some cartoons were published in Simplizissimus from Munich (some time between 1914-1823)23. The first one was done by Thomas Heine. It shows that German ladies were infatuated by Tagore and worshipped him though they did not read much of Tagore’ s literature. The second one was painted by Clav Gulbranson. Gulbranson sets this cartoon in the context of the story of Peter pan. It is a kind of a never never land of Peter where German Tagore-Iovers never grow old in age., It is like a fairy land. Peter (Tagore) with ‘Tiger lily’ reminds us of the oriental fairy land, India. These two cartoons reveal the orientalisrn of the then Germany, who fell in love with Tagore (consider the adulation and ovations he received there and the tremendous boost in publications of his literary works in Germany).

Now, if we look at the caricature by Max Beerbohm, “Mr. William Rothenstein warns Mr. Tagore against being spoilt by occidental success:”. It will be obvious that this cartoon is very different from the two German cartoons. Citing two examples of Gaganendranath’s cartoons. “My Love of My Country is as Big as I am” and “The Temple priest sells his benediction”, Abu Abraham the famous cartoonist writes:

his style shows the influence of European masters of art, like Phil May and Max Beerbohm.24

Rothenstein a close friend of Rabindranath visited Calcutta and was the guest of the Tagore’s at their Joraasanko house in 1911.Max and Rothenstein were close friends too. In a letter to Rabindranath (dated July 1,1915), Rothenstein wrote:

… We have had Max Beerbohm and his wife staying with us. They are Keen appreciators of your work …Max, like all satirists, is very sensitive to Beauty and is not readily deceived by make-believe.25

It is quite possible that Max’s works reached Gaganendranath through Rabindranath. But Max’s style was elegant, very subtle and poetic in his approach to characters and situations. The cartoon resembles more of the so called Bengal school (or the nationalistic bourgeois style of Abanindranath and his pupils. The influence could be other way round, I am inclined to believe. Also it is difficult to accept Phil May’s influence on Gaganendranath. Cartoons in the first two decades of the twentieth century have grown into two diametrically opposite principles.

- A distortion of images born from Expressionism, a violent and forceful social and political satire leaning on the edge of hard realism (like Mino Maccari’s work].

- A subtle and lyrical type of caricature ‘represented by the humorous and other-worldly’ drawings of Steinberg.

To which category Gaganendranath belonged? It is difficult to judge, for he did both types of work, but on the whole I think he belonged to the second category.

Max Weber defined “Style” as a kind of “Utopia”, that means the work of art never actually attains it’s goal. Style or form grows out of content, then, we will have to ascertain what actually the content of a work of art is, or what is the goal of the artist? Like any other medium/category of painting cartoon is a medium. And cartoon is:

… the distorted, usually satirical representation of a person or action by exaggeration of characteristic traits..26

Mark Twain thought of the comic as ‘highly individual form of inexorably effective social criticism and self criticism’. And Herzen wrote:

There is no doubt that laughter is one of the most powerful weapons for destruction … 27

Comic is active, always ready to engage in combat. Every content, art form and style has a historical premise. Every new content and form is born out of a new social necessity negating the previous out of date values, the insufficiency of the earlier form and content. A change corresponding to the general intellectual crisis occurs in the theory of art. The art of the nationalistic bourgeois remained stagnant for quite some time. Because of their mythological roots, they were unable to grasp the true reality and beauty, their content and form was indefinite ‘in itself, in contrast to ‘the naive nationalism of the bourgeoisie style, Gaganendranath for the first time raised the problem: that the mythological past to which art was rooted was no longer sufficient in the changing sociopolitical conditions of Bengal. That a different set of relational value between art and society, between art and people, of the immediate situation, could be established.

Comic is active, always ready to engage in combat. Every content, art form and style has a historical premise. Every new content and form is born out of a new social necessity negating the previous out of date values, the insufficiency of the earlier form and content. A change corresponding to the general intellectual crisis occurs in the theory of art. The art of the nationalistic bourgeois remained stagnant for quite some time. Because of their mythological roots, they were unable to grasp the true reality and beauty, their content and form was indefinite ‘in itself, in contrast to ‘the naive nationalism of the bourgeoisie style, Gaganendranath for the first time raised the problem: that the mythological past to which art was rooted was no longer sufficient in the changing sociopolitical conditions of Bengal. That a different set of relational value between art and society, between art and people, of the immediate situation, could be established.

This new relational value system wiped off the difference between the amateur and the professional, between the working artist and the cultured layman. The role of the artist and the layman reversed. The artist no longer wanted to keep a superior position (vis-a-vis their academic and social status] of painting subjects from mythological past, adopting wishy washy style to make the objects and figures float in darkness. As if the world is viewed through closed windows or dropped curtains. Gaganendranath’s world was real, consisting of immediate facts, because he was always in tension with them. He depicted the characters, situations which were familiar to him. The comic is basically rooted in the objective nature of things. The spectator also changed their stand, they wanted to see the milieu of rich people of the colonial oppressors, and not the circumstances of their own constricted lives. Gaganendranath’s art was intended neither for the working class nor for the peasantry, but for the higher, the urban levels of society.

His was the style of progressive realism. Through satire, sometimes violent sometimes subtle, through grotesque figuration, through exaggeration, larger-than-life approach, he initiated an effective social criticism.

Bibliography

1.Ratan Parimoo – The Paintings of the three Tagores:

Abanindranath, Gaganendranath and Rabindranath,

Chronology and comparative study,Baroda,1973.

Popular Aesthetics,Moscow,Vol.2,1917.

2.Max Raphael- Pr-historic Cave Paintings,1945.

London,1963.

3.Nilima Sheikh-‘The Exotic and the ambiguous,

some recurrent tendencies in Modern Indian Painting.

‘VRISCHIK. Year 4, no. 1, March, 1973.

4. A.K. Coomaraswamy – Art and Swadeshi.

5. A.K. Coomoroswamy – ‘Art in Indian Life’ in Cultural Heritage of India, Vo1.3, n.d.

6. Nicas Hodjiniclaou – Art History and Class Struggle,London,1979.

7. John Berger – ‘The Necessity for Uncertainty’,The Marxist Quarterly,

Vol 3, no. 1, January 1956.

8. Ernst Fischer – The Necessity of Art,London,1963.

9. Dinesh Chandra Sen-‘Gaganendranath Thakurer Smrithikatha,

Ananda Bazar Patrika, 16th March,1938

10. Prasanto Pal – Rabi Jibani,Vol.4,1988.

11 Prasanto Pal – Rabi Jibani,Vol.3,1987.

12 Gaganendranath Tagore – Nabo Hullor

(Reform Screams) 1921 .

.13. Rathindranath Tagore – On the Edges of Time,

London,1958

14. Hoffmann and Becatti – Encyclopaedia of World Art,

Vol.3,1960.

15. Jagdish Mittal – ‘Caricature and Comic in Ancient Indian Art’,

Rooplekha,Vol 33,No. 1 and 3 1962 (?)

16 . O.C. Ganguly – Bharoter Shilpo O Amar Katha,

Calcutta,1969.

17. Kamal Sarkar – Rupadakkha Gaganendranath,

Calcutta,1980.

18. Gaganendranath Tagore – Advut Lok (Realm of the Absurd),

Calcutta,1917.

19. Ibid

20 Nepal Mazumdar – Bharate Jatiota 0 Antarjatikata Ebang Rabindranath,

Vol. 1 (Reprint),1983.

21. Kamal Sarkar – Rupadakha Gaganendranath,

Calcutta,1986.

22. St. Nihal Singh – ‘An Evening with Rabindranath Tagore’

(Quoted in Modern Review,July,1921).

23 Shamvunath Das – Rabindranather Vraman Chinta’,

Purashree(Calcutta Municipal Gazette},Special

Issue, May,1978.

24. Abu Abraham(Ed.) – The Indian Cartoons,1988.

25. Mary M.Lago (Ed.) – Imperfect Encounter

(Letters of William Rothenstein and Rabindranath Tagore,

1911-1941),USA,1972.

26. Nicholas Wadley- ‘Cartoon and Caricature’,

The Encyclopaedia of Visual Art,No.10,1983.

27. Alexander Herzen – Quoted by Avner Zis in Foundations of Marxist Aesthetics,Moscow,1977.

Comic is active, always ready to engage in combat. Every content, art form and style has a historical premise. Every new content and form is born out of a new social necessity negating the previous out of date values, the insufficiency of the earlier form and content. A change corresponding to the general intellectual crisis occurs in the theory of art. The art of the nationalistic bourgeois remained stagnant for quite some time. Because of their mythological roots, they were unable to grasp the true reality and beauty, their content and form was indefinite ‘in itself, in contrast to ‘the naive nationalism of the bourgeoisie style, Gaganendranath for the first time raised the problem: that the mythological past to which art was rooted was no longer sufficient in the changing sociopolitical conditions of Bengal. That a different set of relational value between art and society, between art and people, of the immediate situation, could be established.

Comic is active, always ready to engage in combat. Every content, art form and style has a historical premise. Every new content and form is born out of a new social necessity negating the previous out of date values, the insufficiency of the earlier form and content. A change corresponding to the general intellectual crisis occurs in the theory of art. The art of the nationalistic bourgeois remained stagnant for quite some time. Because of their mythological roots, they were unable to grasp the true reality and beauty, their content and form was indefinite ‘in itself, in contrast to ‘the naive nationalism of the bourgeoisie style, Gaganendranath for the first time raised the problem: that the mythological past to which art was rooted was no longer sufficient in the changing sociopolitical conditions of Bengal. That a different set of relational value between art and society, between art and people, of the immediate situation, could be established.

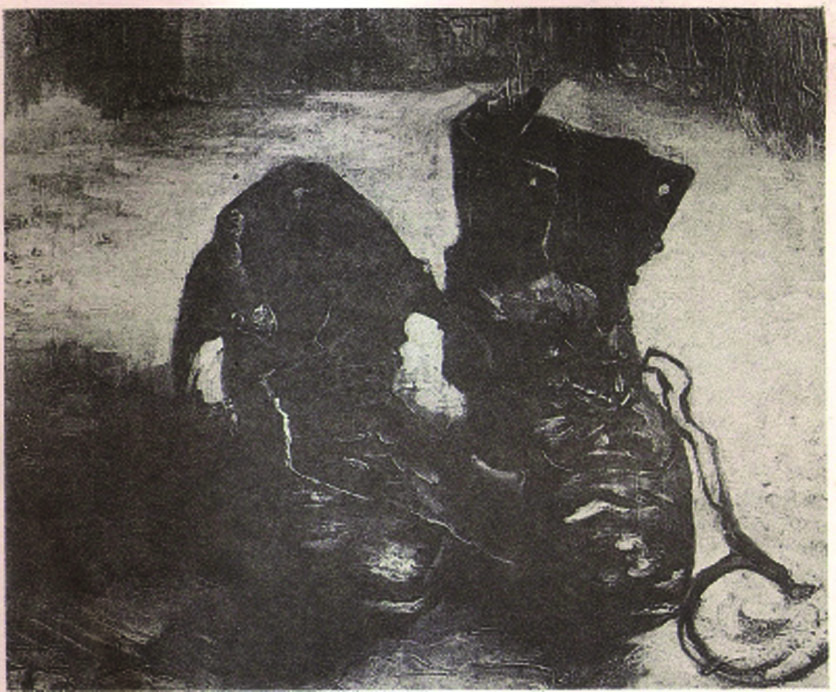

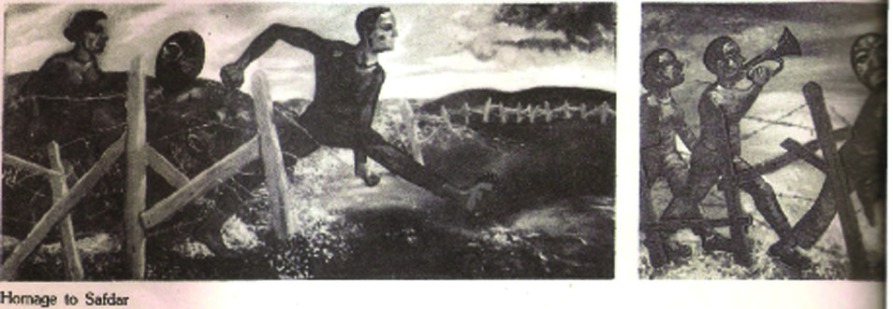

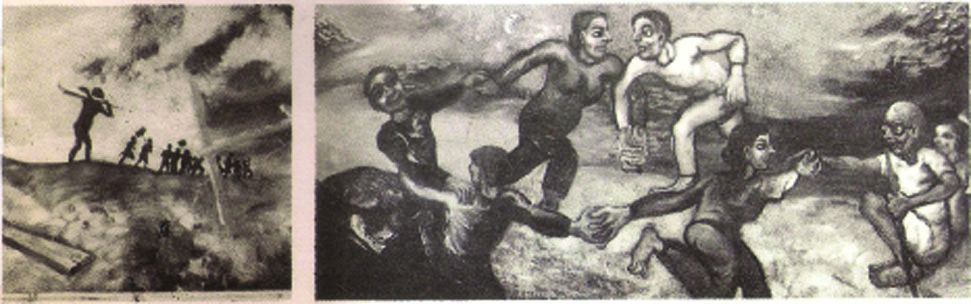

The Burial at Omans

The Burial at Omans A pair of Shoes

A pair of Shoes

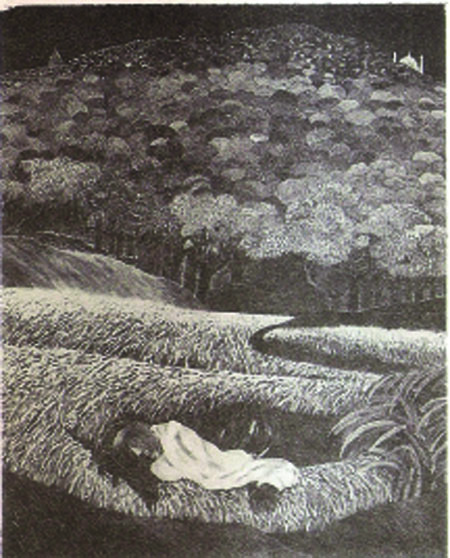

The Child by Nitai Mazumdar

The Child by Nitai Mazumdar